There is no single individual who has influenced the course of the development of art music in contemporary Ghana as much as Dr. Ephraim Amu.”

– J.H. Kwabena Nketia

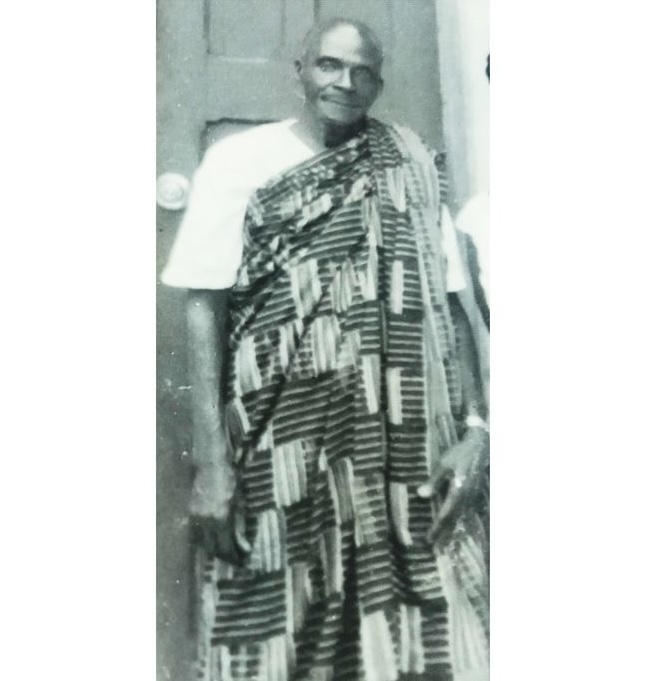

Ephraim Amu (1899-1995) was an internationally renowned musician, musicologist, instrument maker, teacher, philosopher, theologian, committed Christian and preacher.

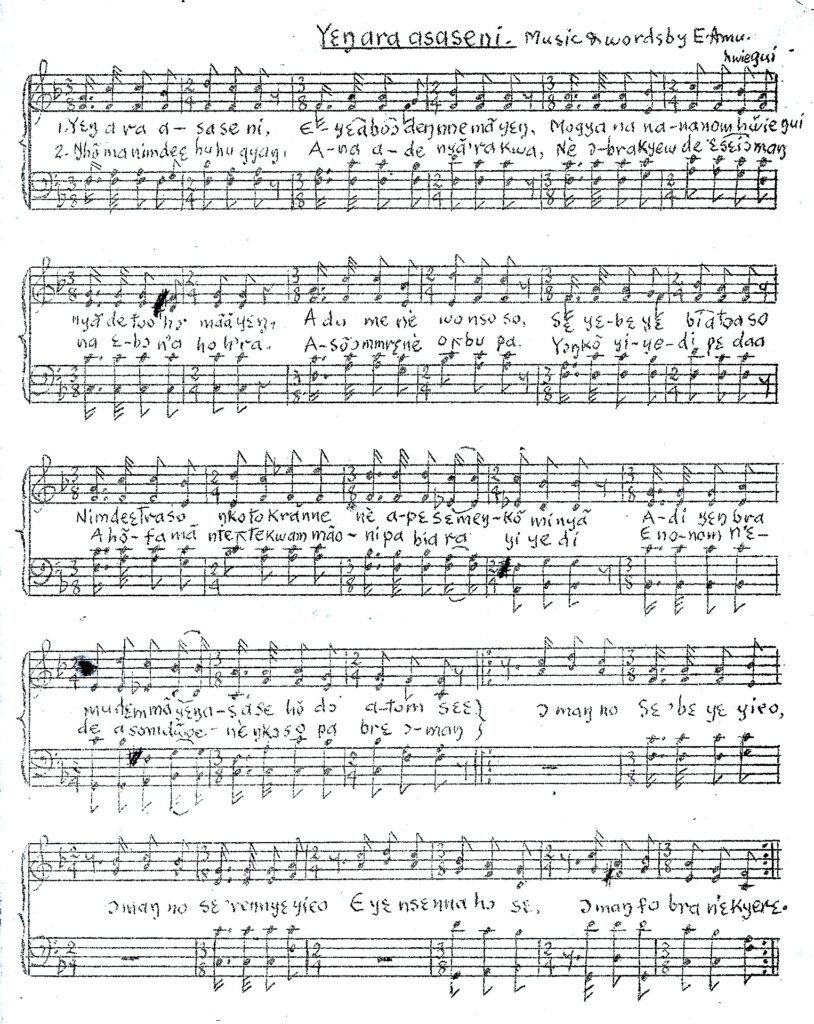

Affectionately called Tata Amu, he composed over 200 works in Eʋe, Twi, Ga and a few early English songs with inspiring lyrics that evince an abiding love for Ghana. His choral works are thought provoking and patriotic, bringing inspiration to generations of Ghanaians. His song Yɛn ara asase ni (This is our own land) continues to inspire a love and respect for the country, and has become a national song played at ceremonial functions. It is also used by Ghana Television as its “end of day” signature signing off. In one of his appraisals, Prof. J.H. Kwabena Nketia (Amu’s chosen ‘godson’ and the scholar easily considered Africa’s premier musicologist during his lifetime) stated; “there is no single individual who has influenced the course of development of art music in contemporary Ghana as much as Dr. Amu.”

Amu pioneered and encouraged the ‘Africanization’ of the church by composing songs rich with African musical features – something the mission hymns lacked. Apart from his musical accomplishments, Amu tried to arouse in the African, consciousness and pride. He believed in igniting the African identity—African ethical, social and political values.

Ephraim Amu was born in Avetile-Peki in the Volta Region of Ghana on September 13, 1899 and died there January 2, 1995. After attending primary and senior schools at Avetile and Blengo respectively, Amu gained admission to the Basel Mission Seminary at Kwahu Abetifi in 1916. He completed his studies in 1919 as a trained Teacher-Catechist.

Amu’s very first music tutor, during his youth, was Mr. Carl Ntem. Later studies were directed by the Rev. J.E Allotey-Pappoe in Amu’s early 20’s during his tenure as music tutor at the Peki-Blengo Senior High School.

In 1937, while working at the Achimota College, Amu traveled to London and continued his composition and music theory studies at the Royal College of Music.

Ephraim Amu taught at Blengo-Peki Senior High School from 1920 to 1925. The subjects he taught included Music, Agriculture, and Needlework to the girls (thinking about the future of the girls). Amu travelled all the way to Koforidua to purchase a harmonium for their music lessons. On his return, he had to carry this on his head for the rest of the journey from Frankadua to Peki, a distance of about 10 miles.

Amu was promoted to the Scottish Mission Seminary at Akropong in 1926. He taught many subjects including, Music, Agriculture, Nature Study and Ewe. It was here that Amu learned Twi proverbs and their meanings from two sons of then Chief Nana Kwasi Akuffo. They taught him drumming and Akuapem traditional culture. Noting its value, Amu introduced drumming into the institution to the utmost chagrin of the authorities. He also composed works for traditional flutes, the Atεntεbεn and Odurugya which he then taught his students, as well as many songs for both male and mixed-voice chorus. It was during this period that Amu published his Twenty-five African Songs (1932).

Amu’s introduction of these cultural activities into this mission institution was unacceptable to the authorities. Coupled with the cultural activities that Amu was involved in, he wore the traditional kente to mount the pulpit, and this broke the camel’s back. The event triggered Amu’s dismissal from Akropong in 1933. It is worthy of note that the kente that caused the displeasure of the Clergy at that time is now made in strips and worn by Reverend Ministers of the Gospel throughout the country and abroad. Further, Ghanaian Presidents from the time of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah (1957) to this day, have worn kente in one way or another as they are sworn in to take up office, and Ghanaian Ambassadors are regularly seen beautifully clad in kente when presenting their letters of credence.

In 1934, Achimota College offered Amu a teaching appointment that allowed him to teach his proud revolutionary and culturally oriented programs. He taught Eʋe, Twi, African Music and drumming in the Lower Primary division of the school. Amu engaged in deeper exploration in the construction of the Atεntεbεn and Odurugya during this time. The instruments evolved as he expanded the range capacities of the instruments, developed a new mouthpiece for the Odurugya, and created the Odurugyaba, the tenor member of the flute ensemble.

Amu traveled to London for music studies at the Royal College of Music in 1937, and upon his return in 1941 Achimota College had been reformed and the Primary division closed down. Amu was thus attached to the Training College. He was assigned to establish a three-year specialist Music course to train Ghanaian teachers who would teach music in Training Colleges, Secondary and Middle Schools, Church Choirs and Singing Bands. The Music School was opened in 1949. Amu continued to teach the very cultural activities for which he was fired at Akropong.

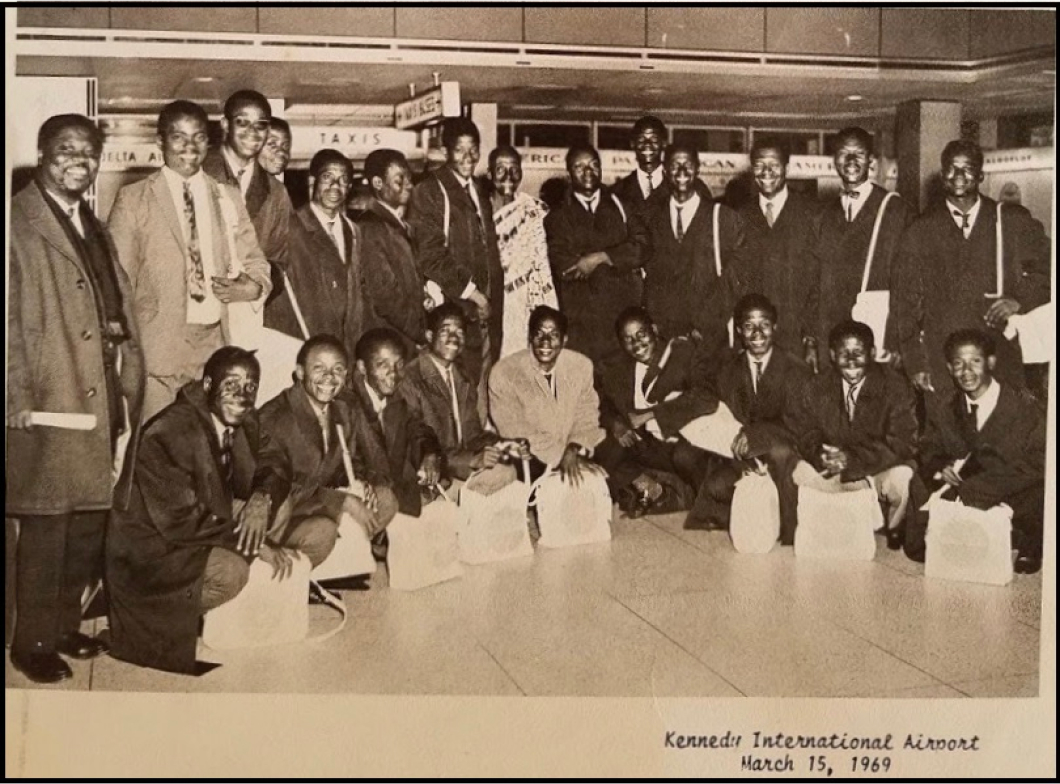

When Kumasi College of Technology, now Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, was established in 1951, the Training College and Music School were moved from Achimota to Kumasi and Amu relocated. He worked here until 1960. He had planned to retire, yet was called back to service at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, (1962 to 1971). In addition to teaching, he was also engaged in research as a Senior Research Fellow dedicating much of his time to the construction and evolution of the Atεntεbεn, Odurugya and Odyurugyaba. It was during this period that Amu took his students to New York to sing at an international choral festival. The standing ovation mid-concert did not prohibit them from finishing their performance.

Amu finally settled home in Peki and spent the rest of his time farming and building up his Nεnyo Choir which he set up in the early 1960s. He did continue to compose, though not nearly as prolifically as earlier in his career. His final composition dates from 1986, nine years prior to his passing in 1995. Amu was given a state funeral, and was laid to rest on the family compound in Peki, as was his wife Beatrice, with him.

Twenty-five African Songs is published – Sheldon Press, London

Amu's work on the instrument construction of the Atεntεbεn, Odurugya and Odurgyaba results in innovated developments that prove to have lasting effects on the viability of the instruments in Ghanaian music and education.

Three Solo Songs with Piano Accompaniment is published – Presbyterian Book Depot, Accra

University of Ghana awards Amu an Honorary Doctorate Degree in Music

Amu and the University of Ghana Chorus participate in the Second International Choral Festival at Lincoln Center, NY, receiving a standing ovation.

Amu receives the Grand Medal of the Republic of Ghana.

The State awards Amu membership in the Order of the Volta.

The University of Science and Technology confers on Amu an Honorary Doctorate Degree.

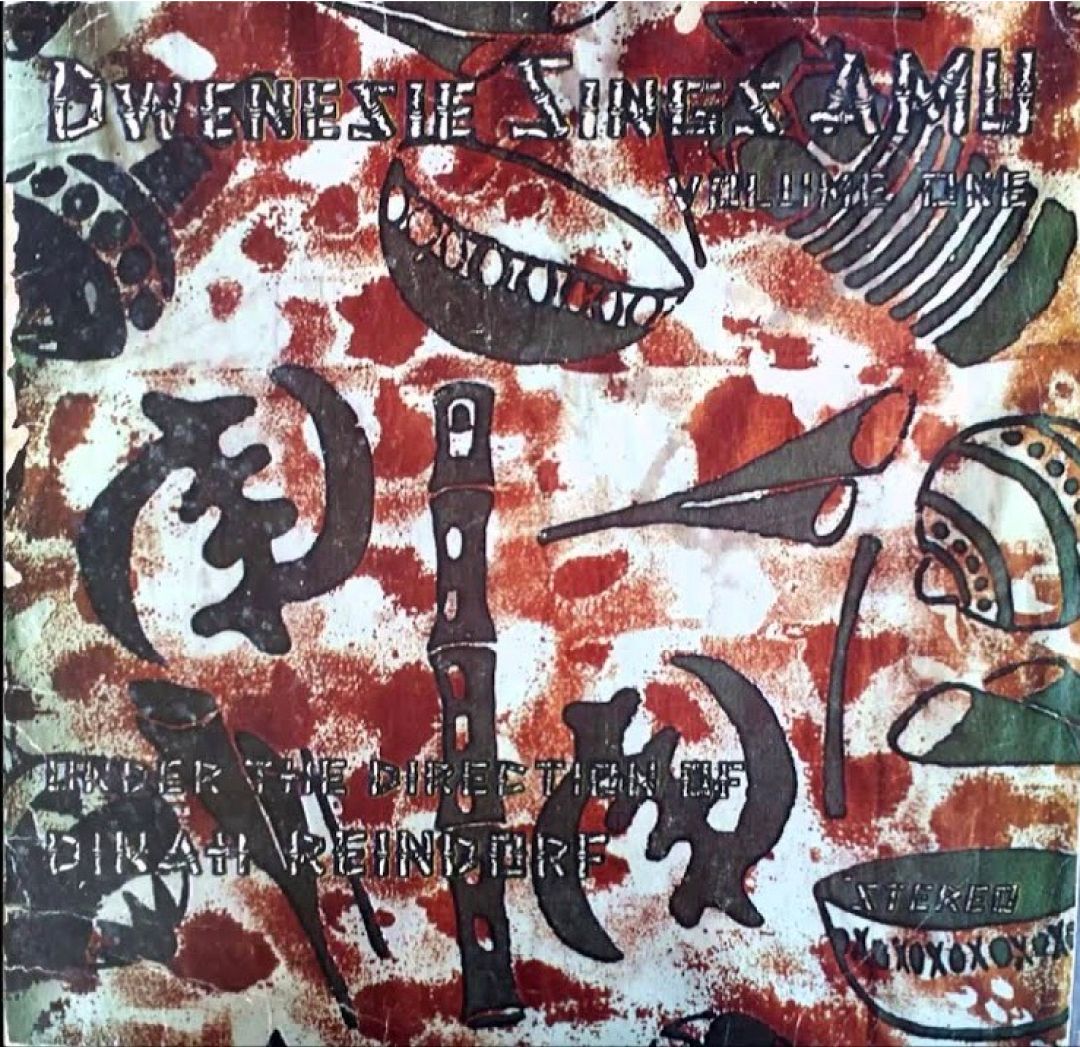

The first recording of Amu’s works, Dwenesie Sings Amu (DSA 6001), is released, directed by Mrs. Dinah Reindorf.

Amu is awarded UNESCO Music Prize, at a ceremony in Bratislava.

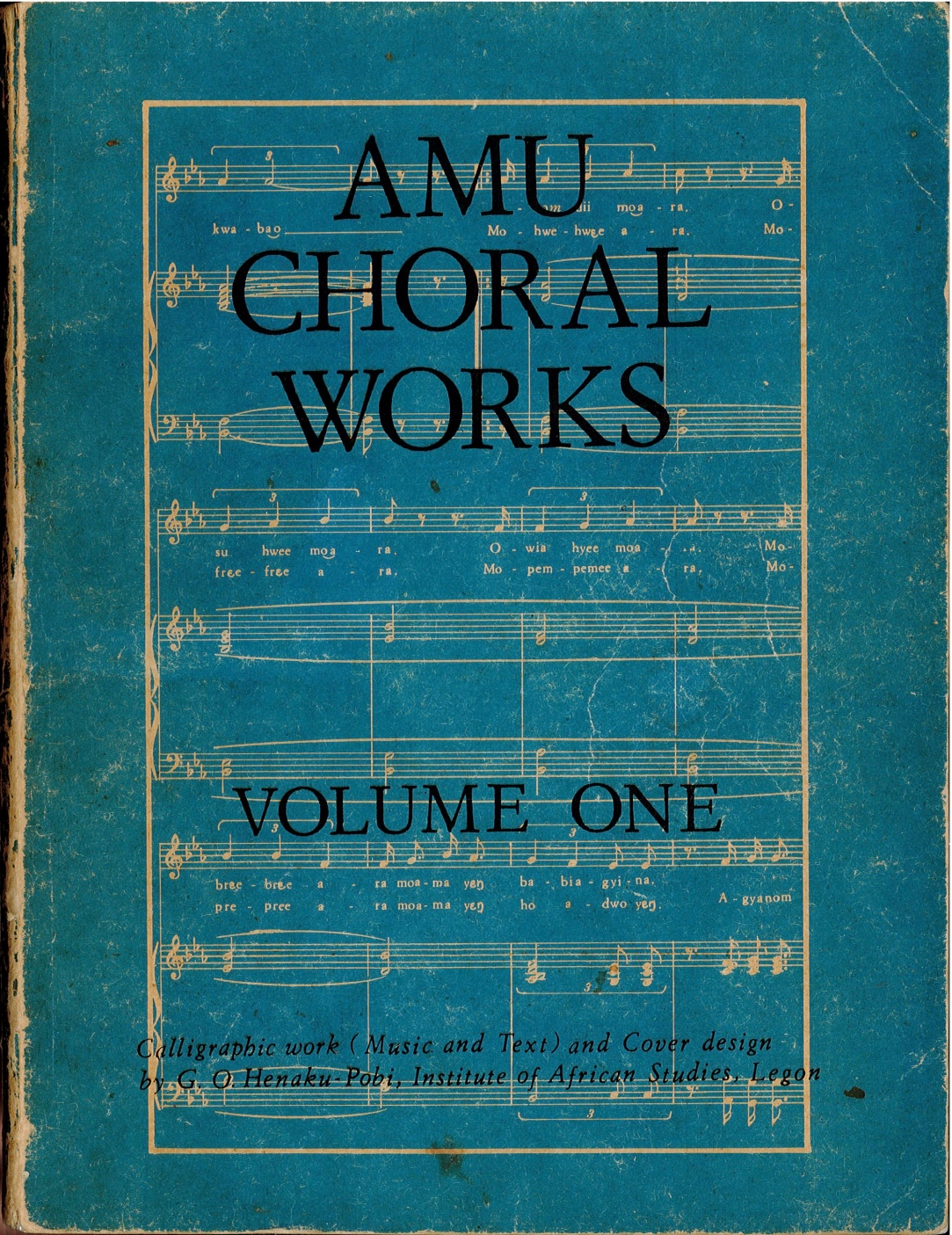

Amu Choral Works, Volume 1 is published – Waterville Press, London

A Tugboat is named Ephraim Amu by Ghana Ports and Highways Authority.

The International Centre for African Music and Dance under the auspices of Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences, institutes the Ephraim Amu Memorial Lectures that continue to be held yearly.

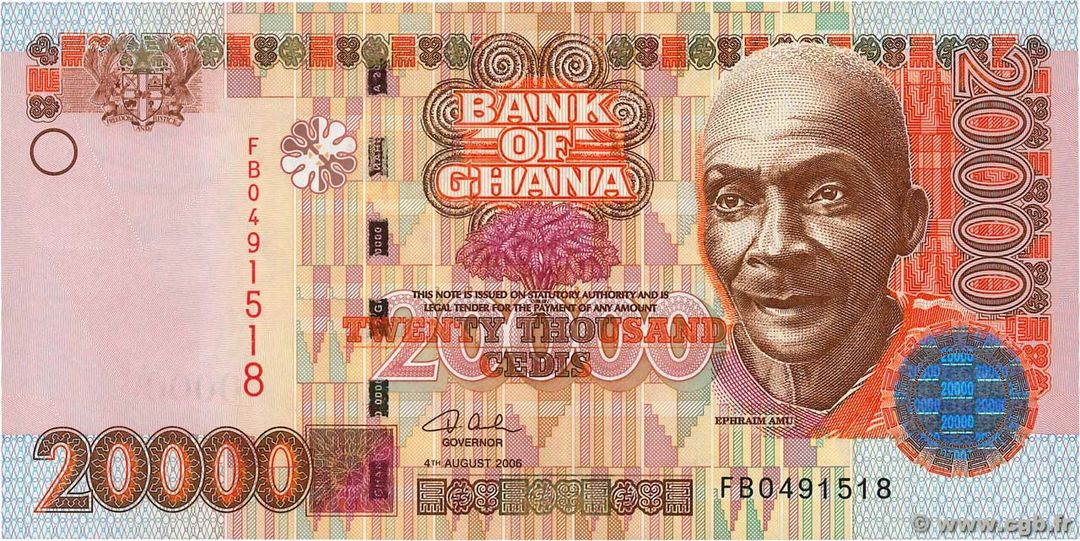

Amu’s portrait is embossed on the Twenty Thousand Ghana Cedi note, the highest denomination at the time, by the government of Ghana.

In the Spring of 2014, Felicia Sandler organized an international festival celebrating the music of Dr. Ephraim Amu at the New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) and Tufts University, in the Greater Boston Area, MA, USA. amufestival.weebly.com It was a collaborative venture comprised of Symposium, Concert, Workshops, and Panel Discussion, with a number of satellite events taking place before and after the main proceedings.

Kofi Agawu, keynote speaker, expressed regret and some frustration that the music of Dr. Amu is so difficult to access—that there is no authoritative collection of all his compositions. There was a consensus among those present that the first order of business post Festival should be the development of a critically informed performance edition of Amu’s complete works. As the one who had prepared Amu’s scores for the Festival choirs, Sandler was approached with the prospect that she develope the scores in the new edition. She agreed to do so in consultation with a team of Ghanaian musicologists, choir directors, and linguists. All enthusiastically signed on for the work ahead.

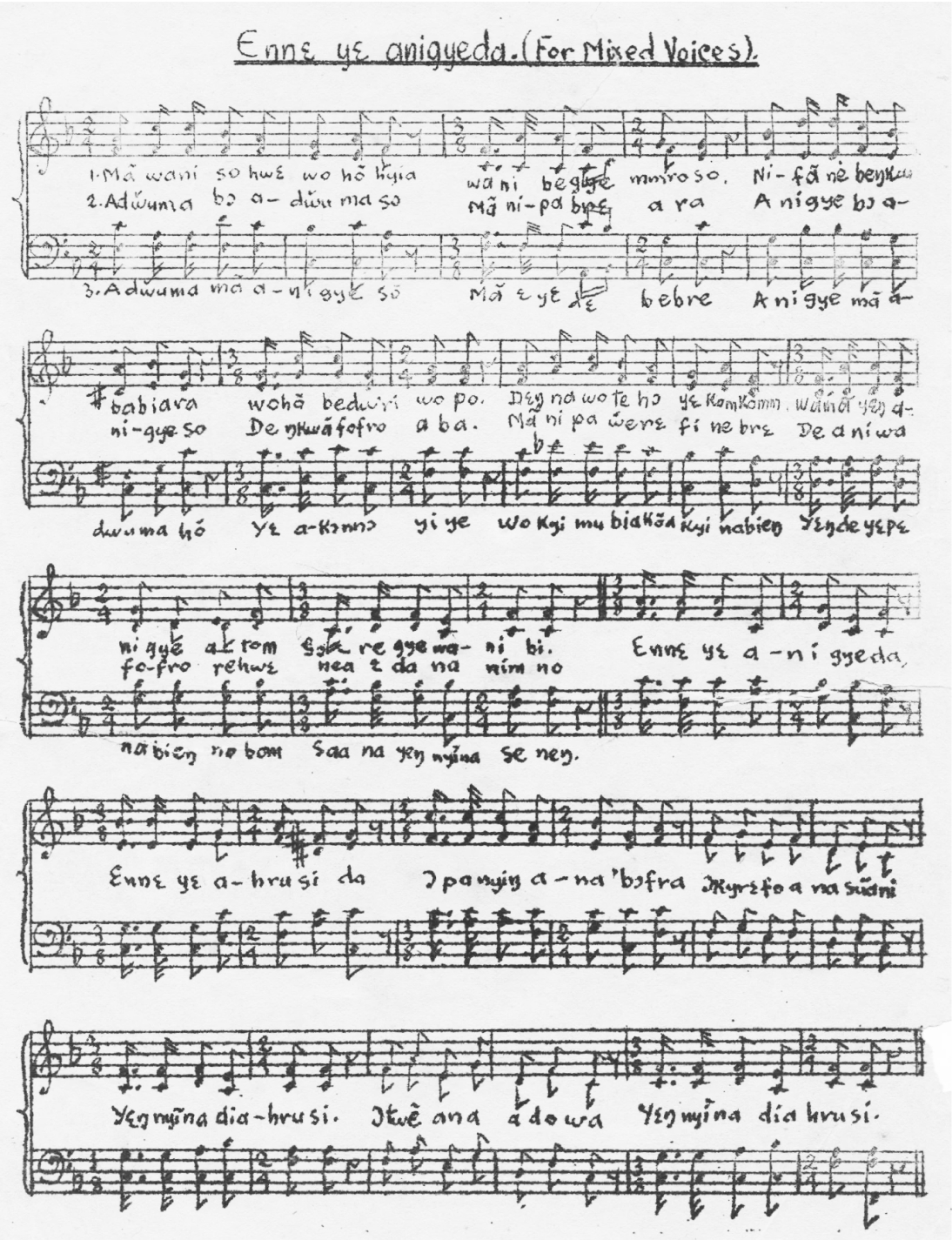

Work began with the compiling of all available musical score sources. Roughly one quarter of Amu’s works had been published in seven collections, all out of print and containing many errors. Three are dedicated solely to his work: Twenty-five African Songs (1932), Three Solo Songs with piano accompaniment (1961), Pipes and Drums (1969), and Amu Choral Works Volume 1 (1993).

Some works are also available in scholarly theses and hymnbooks (Amu 1984; Dor 1992). The autograph scores fill the void for the other three quarters of Amu’s music, yet these are nowhere near publishable.

Twenty-two of his 224 titles are missing. The new edition then is comprised of 202 scores, primarily choral works, with compositions for traditional flutes, solo voice with piano, and brass band as well.In addition to scores in staff notation, Amu’s music is also found in other formats. Tonic-solfa scores have been made by some choir directors, or by skilled choristers seeking the notation with which they are more comfortable, and these editions circulate. There are also unpublished editions of Amu’s works in staff notation created by musicians who sought to remedy errors identified in the published versions, or who determined that a 6/8 time signature was preferable to Amu’s 2/4 meter with relevant triplets signs. Apart from the use of tonic-solfa scores, which is widespread for choral singing in the country, the most typical practice in Ghana is for the choir director to learn from a score, and then teach the music to the singers by rote.

Musical scores reflect a composer’s intentions, especially if the score is in the composer’s own hand. But sometimes they can be spare, especially if the composer knows he can use rehearsal time to make his wishes known. For this reason, we relied heavily on recordings, especially those conducted by Dr. Amu himself, when making the newly engraved scores.

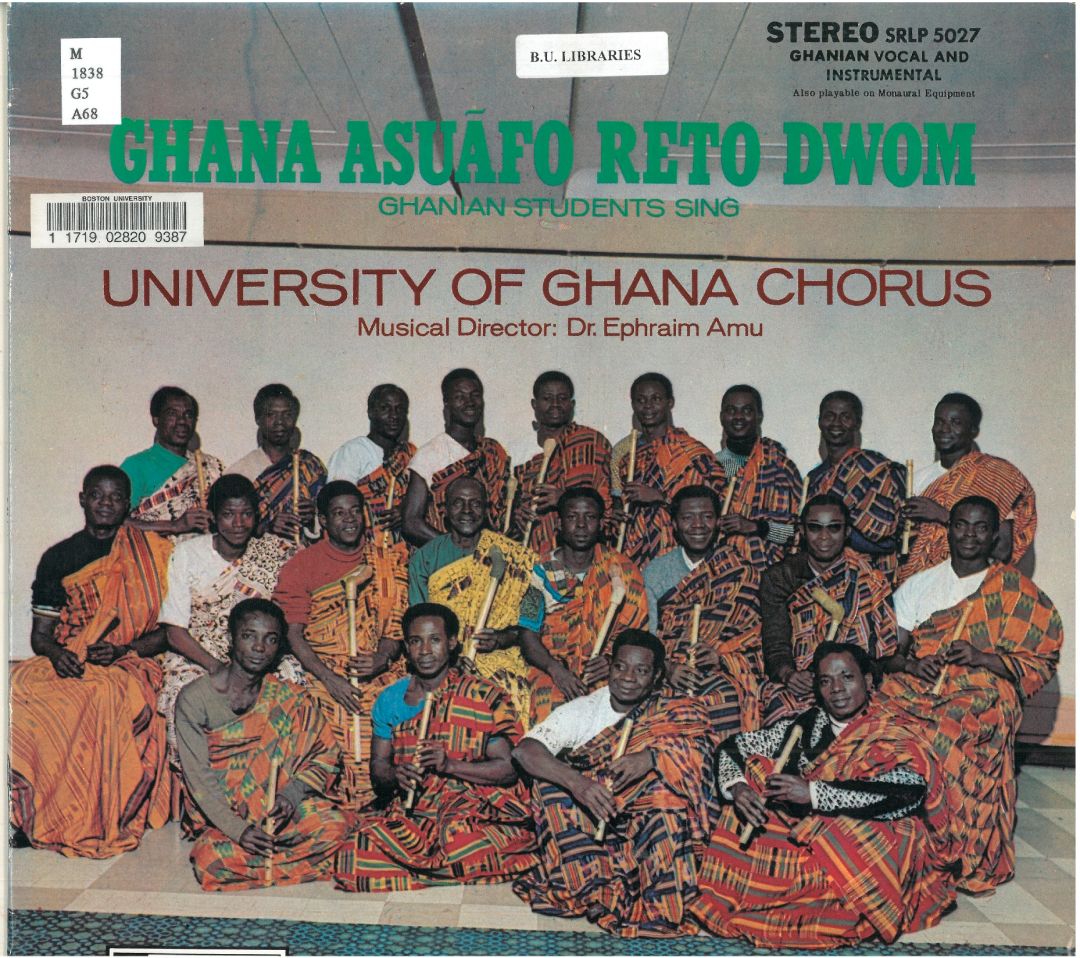

We have recordings for sixty-four different works. Apart from two commercial recordings—Ghana Asuafo Reto Dwom, The University of Ghana Chorus directed by Dr. Ephraim Amu (1977), and Dwenesie Sings Amu, directed by Mrs. Dinah Reindorf (1977)—we relied most heavily on a few unpublished cassettes. These include the 1969 Lincoln Center recording of the University of Ghana conducted by Dr. Amu, the recording of the University of Ghana Chorus, directed by Dr. Willie Anku (2009), the recording of the West Volta Presbytery choir directed by Dr. Misonu Amu (2010), and a series of ad-hoc recordings housed at the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation sung by various schools and community choirs in the country.

After assembling and scanning all the print sources, Sandler compared the various sources to one another and made a first draft, all the while keeping a running tally of any discrepancies between the sources. She then listened to available recordings, and generated second draft, favoring the performance tradition revealed in recordings. The decision to favor the performance tradition in the editing process was a very practical one and is taken up at length in the Critical Report. [link?] The second draft was then sent to Misonu Amu in PDF along with critical notes, a list of unresolved discrepancies between the scores, and an audio file of the computer-generated score. Together, Sandler and Amu mended lyrics and music, then proofread a third draft for mistakes. The final draft then was proofread in hardcopy, and sent to proof-reading team members for comments, questions, and amendments.

The new seven-volume scholarly performance edition presents Amu’s works according to voicing, and chronologically within each volume, as follows:

With the assistance of Mr. Moses Adjei at the GBC, and Mrs. Dinah Reindorf at the Dwenesie Music Institute, we were able to amass vintage recordings for sixty-four titles, along with those in Misonu Amu’s audio library. Twenty-one songs needed to be recorded for Volume 1. Two of the finest choirs in the country signed on to record the missing works: The Harmonious Chorale under the direction of Mr. James Varrick Armaah, and the Greater Accra Mass Choir under the direction of Rev. Newlove Annan.

Translations

Each song has been translated into English. There are four translators on our team. The Rev. Philip T. Laryea and Mr. Francis Akutey-Baffoe are translating the Twi songs, and Dr. Misonu Amu and Rev. Gilbert K. Ansre are translating the Eʋe songs. Amu is translating all Ga lyrics.

Pronunciation Guides

Many choral publications include a pronunciation guide for singers using the International Phonetic Alphabet so that those unfamiliar with the language have an idea for how to pronounce the syllables. In our case, we are providing audio guides. Because Eʋe, Twi, and Ga are all tonal languages, where syllables rise or fall matters in regard to text meaning. By hearing the words spoken, scholars can explore the manner in which Amu composes his melodic contours to reflect the text tone and speech rhythms.

Facsimiles & Out-of-Print Publications / Critical Notes and Report

It is essential that performers and scholars know the editorial decisions made by the team and rationales for alterations in the original scores. This is why the autograph scores and early print scores have been made available, and why we have provided the Critical Report and Critical Notes. Amu was a pathfinder, an architect of a brand-new idiom. A lively discourse can easily emerge around this repertoire with the transparency that the Report and Notes provide.

Next Steps

Volume 1 is now available, and the Harmonious Chorale and Greater Accra Mass Choir are busy recording those works for which no vintage recordings are available. Work is now underway on Volume 2. Sign up for the newsletter to stay abreast of updates. There are a number of avenues for supporting the Amu Score Project. Please see the Support Page to see how.

Retired Research Fellow, Institute of African Studies, Legon Ghana West Africa

Professor of Music – The New England Conservatory of Music, Boston MA USA

Distinguished Professor of Music, City University of New York, New York NY USA

Professor Emeritus of Ethnomusicology, Tufts University, Medford MA USA

Professor of Music and the McDonnell Barksdale Chair of Ethnomusicology, University of Mississippi, Oxford MI USA

Associate Professor of African Theology, Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture, Akropong-Akuapem Ghana West Africa

Professor Emeritus of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon Ghana West Africa

African Language Program Preceptor, Department of African and African American Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge MA USA

Executive Director of the African Bridge Network, Newton MA USA

The Greater Accra Mass Choir, Accra Ghana, West Africa

Director of the Harmonious Chorale

International Centre for African Music and Dance Legon Ghana West Africa

School of Performing Arts, University of Ghana Legon Ghana West Africa